NOVEMBER 3RD, 2022

A little after 7:30 in the morning on Wednesday, December 7, 1887, in the aftermath of remarkably strong northeasterly winds, Captain William A. Martin instructed the crew of the Eunice H. Adams, a whaling ship from Massachusetts, to anchor in cerulean water roughly 24 feet deep, close to Port Royal, South Carolina. Around 9 a.m., Charles Hamilton, a desperate crew member, jumped overboard — deserting his post, with the intention of swimming to land. He was intercepted mid-route by another ship, which returned him to the leaking brig he had tried to escape.

Later that day, an act of near-mutiny occurred. According to the ship’s logbook, a signed letter from the majority of the crew was sent ashore to Port Royal authorities. In it, the men complained that the vessel they sailed on was “unseaworthy,” unhappy with the unplanned stop and delay for repairs merely months into their voyage, in the hope that they’d be released from duty. Authorities did nothing. A sheet of rain beat down on the Eunice H. Adams, and the miserable crew was forced to continue to carry on to Cabo Verde, an archipelago on the westernmost point of Africa.

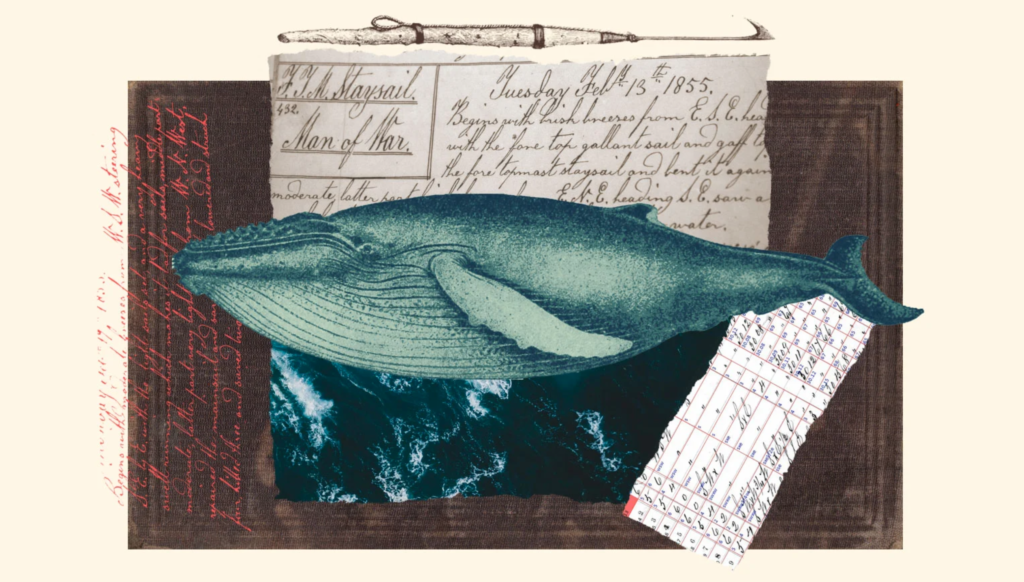

Logbooks, like the nearly 200-page document kept aboard the Eunice H. Adams, served as legal reports, necessary for insurance claims, which meant log keepers kept exhaustive records of the crew’s day-to-day exploits. They tracked the ship’s location, other vessels encountered, and both weather and sea conditions along the routes they sailed. But they also kept clues for the future: Stored within the pages of the 18th and 19th-century whaling logbooks is a cache of ancient weather records, meticulously logged by crews traversing the world’s oceans.

“One of the most important pillars in understanding how events are, or are not, changing is observations,” said Stephanie Herring, a climate attribution scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. “These historical data collection efforts help us extend back the historical record so we can better see what changes might be ‘natural,’ and which we might be driving due to human influence.”

Researchers believe that these handwritten whaling logbooks could be novel guides to understanding the course of climate change. By seeing how the climate once was, they can better understand where it’s going. “This is the language of the sea,” said Timothy Walker, a historian at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth. “The whaling industry is the best documented industry in the world.” Walker and Caroline Ummenhofer, an oceanographer and climate scientist with the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, are working with a team of scientists and volunteers mining archival documents to help inform temperature and weather models — weaving records from a nearly-obsolete industry with modern climate predictions.

Analyzing nearly 54,000 daily weather records from whaling ships, the Woods Hole historic whaling project has mined 110 logbooks to date, from a total cache of about 4,300. The data includes everything from latitude and longitude to ship direction, wind direction and speed, sea state, cloud cover, and general weather. The records are housed in private and public collections across New England, once a key hub for whaling ships returning from across the globe. Those results have been codified and added to a database that cross-compares the data points from these records with modern global wind patterns, doing things like compiling wind observations made in a specific area during a clear period of time. Large-scale wind patterns influence rainfall, drought, floods, and extreme storms — and more accurate measures of these patterns increases the accuracy of today’s forecasts.

“Whalers go to places where other ships don’t go. The whalers are going out in the middle of nowhere,” said Walker. “That’s great from the perspective of weather data collection, because they’re often the only people reporting weather from 200 or 300 years ago, from the regions where they happen to be hunting whales.”

Walker says they’re currently using these documents to identify geographic ranges where the strongest winds were encountered by whalers and comparing the strength of those wind patterns in the same areas in recent years.

With that data, the team hopes to establish a baseline for long-term wind patterns in remote parts of the world where “very few” instrumental data sets prior to 1957 exist. Currently, the project is only focused on wind data, but they hope to eventually focus on other information in the logs such as rainfall, cloudiness, the condition of the sea, or whether the surface was choppy or calm on a given day. The more data points they collect, the better the accuracy of existing climate models — a 2020 study published in the journal Nature found that a lack of predictability in wind patterns above many of the world’s oceans has led to unreliable rain forecasts.

Via: Grist

Text by: Ayurella Horn-Muller