Most mornings, Danny Kennedy hops on a bike with orange saddlebags and rides half an hour from his home to Oakland’s Jack London Square. He makes for quite a picture cruising down Telegraph Avenue, decked out as he often is in an orange helmet, orange jacket and orange leather Adidas shoes. When he arrives at his office, he often makes his rounds on an orange indoor bike. (He’s not joking around with the orange thing.) Though Kennedy was once a young environmental activist documenting the horrors of the oil and mining industries, he’s now a 41-year-old company man. The orange that he wears daily — which extends even to the checks on his shirts, and which drives his wife crazy — is the brand color for his rapidly growing residential solar company, Sungevity, whose revenues grew by a factor of eight in 2010 and doubled again in 2011, and whose employees have grown to 260 from 3 since the company’s inception five years ago.

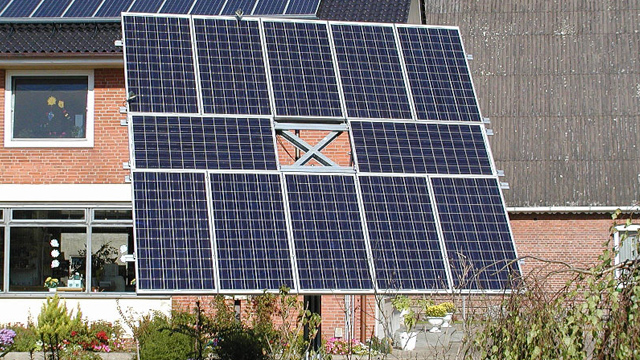

Given that growth, it’s somewhat surprising to learn that Kennedy and Sungevity aren’t taken very seriously by their larger competitors. Kennedy’s activist past and his willingness to wear his commitment to the solar industry quite literally on his sleeve are viewed by some as a liability in an industry desperate to demonstrate its seriousness. Thanks to increased Chinese production of photovoltaic panels, innovative financing techniques, investment from large institutional investors and a patchwork of semi-effective public-policy efforts, residential solar power has never been more affordable. But even with pricing that requires no initial capital outlay from consumers and guarantees lifetime savings — and even occasional opportunities to make money, by selling power back to the grid — Americans still aren’t buying into solar in significant numbers.

Two factors have hurt the industry’s growth. The first is abstract and well ingrained in the American psyche: the negative association of “green” technologies with inefficiency and idealistic, hippie-fueled impracticality. The second is concrete and recent: the sleek, vacant headquarters of Solyndra, the infamous federally subsidized solar-panel manufacturer that went bankrupt in 2011. The glassy campus sits just off the Nimitz Freeway, visible to commuters between San Francisco and Silicon Valley as they battle rush-hour traffic each morning, surreptitiously checking their phones.

Though the failure of Solyndra has dominated the political and social discourse around solar power, the reality of the industry — as evidenced by the enormous investments that companies like Google and Bank of America are making in residential solar power — is that it has rapidly become a smart, practical and profitable investment. Despite a lack of widespread acceptance, the market is growing and the competition is getting tight.

Where Kennedy will ultimately fit into all of this remains to be seen. He told me: “We don’t need missionaries anymore. We need mercenaries.” As the industry grows, big investments don’t necessarily flow toward the people with the deepest environmentalist roots. No matter how much orange Kennedy wears or how dedicated to corporate branding he appears to be, his bleeding heart still shows through. Missionary, mercenary: can he — can anyone — be both?

Read the rest at NY Times Magazine.

Photo via Inhabitat